| AAAPOE Campus |

| AAAPOE Campus: 002: History Hall 歷史館 历史馆 002-002: History of Canada from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

Inhabited for millennia by First Nations (aboriginal), the history of Canada has evolved from a group of European

colonies into an officially bilingual (English and French), multicultural federation, having peacefully obtained

sovereignty from its last colonial possessor, the United Kingdom. France sent the first large group of settlers in

the 17th century, but Canada came to be dominated by the British until the country attained full independence in

the 20th century. Its history has been affected by its inhabitants, its geography, and its relations with the outside

world.

colonies into an officially bilingual (English and French), multicultural federation, having peacefully obtained

sovereignty from its last colonial possessor, the United Kingdom. France sent the first large group of settlers in

the 17th century, but Canada came to be dominated by the British until the country attained full independence in

the 20th century. Its history has been affected by its inhabitants, its geography, and its relations with the outside

world.

History of Canada

New France

Canada under British

Imperial control

(1764-1867)

Post-Confederation

Canada (1867-1914)

Canada in the World Wars

and Interwar Years

History of Canada

(1945-1960)

History of Canada

(1960-1981)

History of Canada

(1982-1992)

History of Canada

(1992-Present)

Military history

Economic history

Constitutional history

History of the monarchy

Timeline

New France

Canada under British

Imperial control

(1764-1867)

Post-Confederation

Canada (1867-1914)

Canada in the World Wars

and Interwar Years

History of Canada

(1945-1960)

History of Canada

(1960-1981)

History of Canada

(1982-1992)

History of Canada

(1992-Present)

Military history

Economic history

Constitutional history

History of the monarchy

Timeline

History of Canada

New France

Canada under British

Imperial control

(1764-1867)

Post-Confederation

Canada (1867-1914)

Canada in the World Wars

and Interwar Years

History of Canada

(1945-1960)

History of Canada

(1960-1981)

History of Canada

(1982-1992)

History of Canada

(1992-Present)

Military history

Economic history

Constitutional history

History of the monarchy

Timeline

New France

Canada under British

Imperial control

(1764-1867)

Post-Confederation

Canada (1867-1914)

Canada in the World Wars

and Interwar Years

History of Canada

(1945-1960)

History of Canada

(1960-1981)

History of Canada

(1982-1992)

History of Canada

(1992-Present)

Military history

Economic history

Constitutional history

History of the monarchy

Timeline

| Viking colonisation site at L'Anse-aux-Meadows |

European contact

There are several reports of contact made before Christopher Columbus between the first peoples and those

from other continents. The case of Viking contact is supported by the remains of a Viking settlement in L'Anse aux

Meadows, Newfoundland. This may well have been the place Icelandic Norseman Leifur Eiríksson referred to as

Vinland around 1000 AD.

The presence of Basque cod fishermen and whalers, just a few years after Columbus, has also been cited, with

at least nine fishing outposts having been established on Labrador and Newfoundland. The largest of these

settlements was Red Bay, where several stations were established. Basque whaling began in southern

Labrador in mid-16th century.

There are several reports of contact made before Christopher Columbus between the first peoples and those

from other continents. The case of Viking contact is supported by the remains of a Viking settlement in L'Anse aux

Meadows, Newfoundland. This may well have been the place Icelandic Norseman Leifur Eiríksson referred to as

Vinland around 1000 AD.

The presence of Basque cod fishermen and whalers, just a few years after Columbus, has also been cited, with

at least nine fishing outposts having been established on Labrador and Newfoundland. The largest of these

settlements was Red Bay, where several stations were established. Basque whaling began in southern

Labrador in mid-16th century.

The next European explorer acknowledged as landing in what is now Canada was John Cabot, who landed somewhere on the coast of North America (probably

Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island) in 1497 and claimed it for King Henry VII of England. Portuguese and Spanish explorers also visited Canada, but the French first

began to explore further inland and set up colonies, beginning with Jacques Cartier in 1534. An attempt at settlement was made in 1600 at Tadoussac; the settlement

failed, but Tadoussac remained a trading post.[1] Under Samuel de Champlain, the first French settlement was made in 1605 at Port-Royal (today's Annapolis Royal, Nova

Scotia), and in 1608 the heart of New-France, which later grew to be Quebec City, was established. The French claimed Canada as their own, and 6,000 settlers arrived,

settling along the St. Lawrence and in the Maritimes. Britain also had a presence in Newfoundland, and with the advent of settlements they claimed the south of Nova Scotia

as well as the areas around the Hudson Bay.

The first contact with the Europeans was disastrous for the first peoples. Explorers and traders brought European diseases, such as smallpox, which killed off entire

villages. Relations varied between the settlers and the Natives. The French befriended several Algonquin nations, including the Huron peoples and nations of the Wabanaki

Confederacy, and entered into a mutually beneficial trading relationship with them. The Iroquois, however, became dedicated opponents of the French, and warfare between

the two was unrelenting, especially as the British armed the Iroquois in an effort to weaken the French.

The first agricultural settlements were located around the French settlement of Port Royal in what is now Nova Scotia. The population of Acadians, as this group became

known, reached 5,000 by 1713.

See also: Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact, French colonization of the Americas, and British colonization of the Americas

Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island) in 1497 and claimed it for King Henry VII of England. Portuguese and Spanish explorers also visited Canada, but the French first

began to explore further inland and set up colonies, beginning with Jacques Cartier in 1534. An attempt at settlement was made in 1600 at Tadoussac; the settlement

failed, but Tadoussac remained a trading post.[1] Under Samuel de Champlain, the first French settlement was made in 1605 at Port-Royal (today's Annapolis Royal, Nova

Scotia), and in 1608 the heart of New-France, which later grew to be Quebec City, was established. The French claimed Canada as their own, and 6,000 settlers arrived,

settling along the St. Lawrence and in the Maritimes. Britain also had a presence in Newfoundland, and with the advent of settlements they claimed the south of Nova Scotia

as well as the areas around the Hudson Bay.

The first contact with the Europeans was disastrous for the first peoples. Explorers and traders brought European diseases, such as smallpox, which killed off entire

villages. Relations varied between the settlers and the Natives. The French befriended several Algonquin nations, including the Huron peoples and nations of the Wabanaki

Confederacy, and entered into a mutually beneficial trading relationship with them. The Iroquois, however, became dedicated opponents of the French, and warfare between

the two was unrelenting, especially as the British armed the Iroquois in an effort to weaken the French.

The first agricultural settlements were located around the French settlement of Port Royal in what is now Nova Scotia. The population of Acadians, as this group became

known, reached 5,000 by 1713.

See also: Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact, French colonization of the Americas, and British colonization of the Americas

New France 1604–1763

After Champlain's

founding of Quebec City

in 1608, it became the

capital of New France.

The coastal

communities were

based upon the cod

fishery, and the economy

along the St. Lawrence

River was based on

farming. French

voyageurs travelled deep

into the hinterlands (of

what is today Quebec,

Ontario, and Manitoba)

trading guns,

gunpowder, cloth,

knives, and kettles for

beaver furs. The fur trade

only encouraged a small

population, however, as

minimal labour was

required. Encouraging

settlement was difficult,

and while some

immigration did occur, by

1759 New France only

had a population of

some 65,000.

New France had other

problems besides low

immigration. The French

government had little

interest or ability in

supporting their colony,

and it was mostly left to

its own devices. The

economy was primitive,

After Champlain's

founding of Quebec City

in 1608, it became the

capital of New France.

The coastal

communities were

based upon the cod

fishery, and the economy

along the St. Lawrence

River was based on

farming. French

voyageurs travelled deep

into the hinterlands (of

what is today Quebec,

Ontario, and Manitoba)

trading guns,

gunpowder, cloth,

knives, and kettles for

beaver furs. The fur trade

only encouraged a small

population, however, as

minimal labour was

required. Encouraging

settlement was difficult,

and while some

immigration did occur, by

1759 New France only

had a population of

some 65,000.

New France had other

problems besides low

immigration. The French

government had little

interest or ability in

supporting their colony,

and it was mostly left to

its own devices. The

economy was primitive,

Wars in the colonial era

Main article: French and Indian Wars

While the French were well established in large parts of Eastern Canada, Britain had control over the Thirteen Colonies to the south; and laid claim (from 1670, via the Hudson's Bay Company) to

Hudson Bay, and its drainage basin (known as Rupert's Land).

Main article: French and Indian Wars

While the French were well established in large parts of Eastern Canada, Britain had control over the Thirteen Colonies to the south; and laid claim (from 1670, via the Hudson's Bay Company) to

Hudson Bay, and its drainage basin (known as Rupert's Land).

| Map of New France made by Samuel de Champlain on 1612 |

| and much of the population was involved in little more than subsistence agriculture. The colonists also engaged in a long running series of wars with the Iroquois. |

Britain and France

repeatedly went to war in

the 17th and 18th

centuries and made their

colonial empires into

battlefields. Numerous

naval battles were fought

in the West Indies; the

main land battles were

fought in and around

Canada. The first areas

won by the British were

the Maritime provinces.

After Queen Anne's War,

Nova Scotia, other than

Cape Breton, was ceded

to the British by the

Treaty of Utrecht. This

gave Britain control over

thousands of

French-speaking

Acadians. Not trusting

these new subjects, who

repeatedly proclaimed

their neutrality, the British

first tried to dilute their

numbers by bringing in

Protestant settlers from

Europe. Finally the

British ordered the Great

Upheaval of 1755,

deporting about 12,000

Acadians to destinations

throughout their North

American holdings. Many

settled in southern

Louisiana, creating the

Cajun culture there.

Some Acadians

managed to hide and

others eventually

returned to Nova Scotia,

but they were far

outnumbered by a new

migration of Yankees

from New England who

transformed Nova Scotia.

repeatedly went to war in

the 17th and 18th

centuries and made their

colonial empires into

battlefields. Numerous

naval battles were fought

in the West Indies; the

main land battles were

fought in and around

Canada. The first areas

won by the British were

the Maritime provinces.

After Queen Anne's War,

Nova Scotia, other than

Cape Breton, was ceded

to the British by the

Treaty of Utrecht. This

gave Britain control over

thousands of

French-speaking

Acadians. Not trusting

these new subjects, who

repeatedly proclaimed

their neutrality, the British

first tried to dilute their

numbers by bringing in

Protestant settlers from

Europe. Finally the

British ordered the Great

Upheaval of 1755,

deporting about 12,000

Acadians to destinations

throughout their North

American holdings. Many

settled in southern

Louisiana, creating the

Cajun culture there.

Some Acadians

managed to hide and

others eventually

returned to Nova Scotia,

but they were far

outnumbered by a new

migration of Yankees

from New England who

transformed Nova Scotia.

| The Death of General Wolfe at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, part of the Seven Years' War. |

During King George's War, British colonial forces captured the French stronghold of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, but this gain was returned to France under the 1748 Treaty of

Aix-la-Chapelle.

Canada was also an important battlefield in the Seven Years' War, during which Great Britain gained control of Quebec City after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, and Montreal in 1760.

Aix-la-Chapelle.

Canada was also an important battlefield in the Seven Years' War, during which Great Britain gained control of Quebec City after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, and Montreal in 1760.

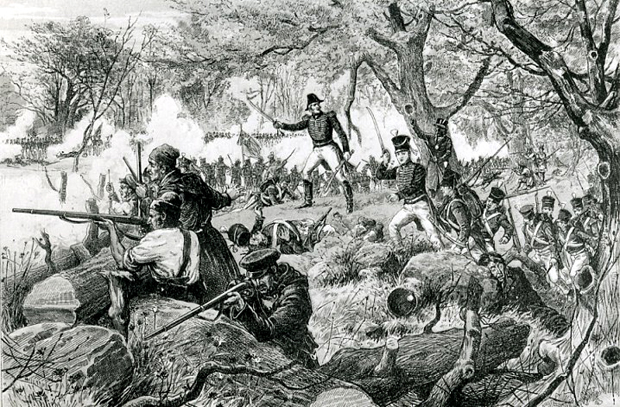

| Henri Julien's artistic rendition of the Battle of Chateauguay, part of the War of 1812 |

Canada under British imperial control 1764–1867

Main article: Canada under British Imperial Control (1764-1867)

With the end of the Seven Years' War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris on

February 10, 1763, France ceded almost all of its territory in North America. The new

British rulers left alone much of the religious, political and social culture of the

French-speaking habitants. Violent conflict continued during the next century,

leading Canada into the War of 1812 and a pair of Rebellions in 1837.

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and the United Kingdom

with the British North American colonies being used as pawns.[2] Although the

causes of the war are still being debated by historians, one the most common

assumptions is that the tensions in the maritime region between the United States

and Britain reached a boiling point.[2] Although not as important as the tensions

between the two powers in the maritimes, another speculation is that the United

States went to war with plans of invading Canada and annexing them to the United

States.[2] Another possible reason for the war was the tensions that were rising on

the western front, which was becoming increasingly more difficult to navigate.[2] The

United States Congress declared war on Britain in June 1812, with the majority of

the votes coming from delegates of the south and the west, who believed that the

only way to expand westward would be to defeat Canada, as well as the Natives,

and that would open the west.[2]

The War of 1812 ended with the Treaty of Ghent and the Rush-Bagot agreement of

1817.[2] Neither side saw any land gains or losses; the only people who really lost

were the Natives who fought for the British and were important in turning the U.S.

away from Canada, and they received nothing except to choose between the United

States who would be brutal after the war or the British who may be more charitable.

[2] One thing that the War of 1812 did accomplish was the shifting of American

migration from north into Upper Canada to west into Ohio and Michigan.[2] The war

was another example of Canada rejecting the United States and their idea of

republicanism.[2]

Main article: Canada under British Imperial Control (1764-1867)

With the end of the Seven Years' War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris on

February 10, 1763, France ceded almost all of its territory in North America. The new

British rulers left alone much of the religious, political and social culture of the

French-speaking habitants. Violent conflict continued during the next century,

leading Canada into the War of 1812 and a pair of Rebellions in 1837.

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and the United Kingdom

with the British North American colonies being used as pawns.[2] Although the

causes of the war are still being debated by historians, one the most common

assumptions is that the tensions in the maritime region between the United States

and Britain reached a boiling point.[2] Although not as important as the tensions

between the two powers in the maritimes, another speculation is that the United

States went to war with plans of invading Canada and annexing them to the United

States.[2] Another possible reason for the war was the tensions that were rising on

the western front, which was becoming increasingly more difficult to navigate.[2] The

United States Congress declared war on Britain in June 1812, with the majority of

the votes coming from delegates of the south and the west, who believed that the

only way to expand westward would be to defeat Canada, as well as the Natives,

and that would open the west.[2]

The War of 1812 ended with the Treaty of Ghent and the Rush-Bagot agreement of

1817.[2] Neither side saw any land gains or losses; the only people who really lost

were the Natives who fought for the British and were important in turning the U.S.

away from Canada, and they received nothing except to choose between the United

States who would be brutal after the war or the British who may be more charitable.

[2] One thing that the War of 1812 did accomplish was the shifting of American

migration from north into Upper Canada to west into Ohio and Michigan.[2] The war

was another example of Canada rejecting the United States and their idea of

republicanism.[2]

In 1837, rebellions against the British colonial government took place in both Upper and Lower Canada. In Upper Canada, a band of Reformers under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie took up

arms in a disorganized and ultimately unsuccessful series of small-scale skirmishes around Toronto, London, and Hamilton.

In Lower Canada, a more substantial rebellion occurred against British rule. Both English- and French-Canadian rebels, with some U.S. backing, fought several skirmishes against the authorities. The

towns of Chambly and Sorel were taken by the rebels, and Quebec City was isolated from the rest of the colony. Montreal rebel leader Robert Nelson read a declaration of independence to a crowd at

Napierville in 1838. Les Patriotes, however, were defeated after battles across Quebec. Hundreds were arrested, and several villages were burnt in reprisal.

A new Whig government sent Lord Durham to examine the situation, and his Durham Report strongly recommended responsible government. A less well received recommendation, however, was the

amalgamation of Upper and Lower Canada in order to forcibly assimilate the French speaking population; The Canadas were merged into a single, quasi-federal colony, the United Province of

Canada, with the Act of Union (1840).

Once the United States agreed to the 49th parallel north as the border separating it from western British North America, the British government created the Pacific coast colonies of British Columbia in

1858 and Vancouver Island in 1849. They were eventually united in 1866.

A set of proposals called the Seventy-Two Resolutions were drafted at the 1864 Quebec Conference. They laid out the framework for uniting British colonies in North America into a federation. They

were adopted by the majority of the provinces of Canada and became the basis for the London Conference of 1866. The move towards uniting the British North American provinces and territories

began out of several of concerns; one was English Canadian nationalism which sought to unite the lands into one country. Concerns over U.S. expansion westward which could endanger the British

colonies also helped foster a desire to formally unify the colonies. On a political level, there was a desire for the expansion of responsible government and elimination of the legislative union of Upper

and Lower Canada, and their replacement with provincial legislatures in a federation. This was especially pushed by the liberal Reform movement of Upper Canada and the French-Canadian rouges

in Lower Canada who favoured a decentralized union in comparison to the Upper Canadian Conservative party and to some degree the French-Canadian bleus which favoured a centralized union.[3]

Post-Confederation Canada 1867–1914

Main article: Post-Confederation Canada (1867-1914)

On July 1, 1867, with the passing of the British North America Act by the British Parliament, the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia became a federation, regarded as a kingdom in

her own right.[4] John A. Macdonald had spoken of "founding a great British monarchy" and wanted the newly created country to be called the "Kingdom of Canada."[5] Although it had its monarch in

London, the Colonial Office opposed as "premature" and "pretentious" the term "kingdom." It might antagonize the United States. The term dominion was chosen to indicate Canada's status as a self-

governing colony of the British Empire, the first time it was used in reference to a country.

With the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the new country expanded east, west and north, to assert its authority over a greater territory. A major means to achieve this was the foundation of

the North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police), which patrolled the territories. Manitoba joined the Dominion in 1870, and British Columbia in 1871. Westward expansion

encountered serious resistance from the region's Métis inhabitants, in the form of the Red River Rebellion and the North-West Rebellion. In 1905, Saskatchewan and Alberta were admitted as

provinces.

arms in a disorganized and ultimately unsuccessful series of small-scale skirmishes around Toronto, London, and Hamilton.

In Lower Canada, a more substantial rebellion occurred against British rule. Both English- and French-Canadian rebels, with some U.S. backing, fought several skirmishes against the authorities. The

towns of Chambly and Sorel were taken by the rebels, and Quebec City was isolated from the rest of the colony. Montreal rebel leader Robert Nelson read a declaration of independence to a crowd at

Napierville in 1838. Les Patriotes, however, were defeated after battles across Quebec. Hundreds were arrested, and several villages were burnt in reprisal.

A new Whig government sent Lord Durham to examine the situation, and his Durham Report strongly recommended responsible government. A less well received recommendation, however, was the

amalgamation of Upper and Lower Canada in order to forcibly assimilate the French speaking population; The Canadas were merged into a single, quasi-federal colony, the United Province of

Canada, with the Act of Union (1840).

Once the United States agreed to the 49th parallel north as the border separating it from western British North America, the British government created the Pacific coast colonies of British Columbia in

1858 and Vancouver Island in 1849. They were eventually united in 1866.

A set of proposals called the Seventy-Two Resolutions were drafted at the 1864 Quebec Conference. They laid out the framework for uniting British colonies in North America into a federation. They

were adopted by the majority of the provinces of Canada and became the basis for the London Conference of 1866. The move towards uniting the British North American provinces and territories

began out of several of concerns; one was English Canadian nationalism which sought to unite the lands into one country. Concerns over U.S. expansion westward which could endanger the British

colonies also helped foster a desire to formally unify the colonies. On a political level, there was a desire for the expansion of responsible government and elimination of the legislative union of Upper

and Lower Canada, and their replacement with provincial legislatures in a federation. This was especially pushed by the liberal Reform movement of Upper Canada and the French-Canadian rouges

in Lower Canada who favoured a decentralized union in comparison to the Upper Canadian Conservative party and to some degree the French-Canadian bleus which favoured a centralized union.[3]

Post-Confederation Canada 1867–1914

Main article: Post-Confederation Canada (1867-1914)

On July 1, 1867, with the passing of the British North America Act by the British Parliament, the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia became a federation, regarded as a kingdom in

her own right.[4] John A. Macdonald had spoken of "founding a great British monarchy" and wanted the newly created country to be called the "Kingdom of Canada."[5] Although it had its monarch in

London, the Colonial Office opposed as "premature" and "pretentious" the term "kingdom." It might antagonize the United States. The term dominion was chosen to indicate Canada's status as a self-

governing colony of the British Empire, the first time it was used in reference to a country.

With the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the new country expanded east, west and north, to assert its authority over a greater territory. A major means to achieve this was the foundation of

the North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police), which patrolled the territories. Manitoba joined the Dominion in 1870, and British Columbia in 1871. Westward expansion

encountered serious resistance from the region's Métis inhabitants, in the form of the Red River Rebellion and the North-West Rebellion. In 1905, Saskatchewan and Alberta were admitted as

provinces.

| Strikers from unemployment relief camps climbing on boxcars as part of the On to Ottawa Trek |

| Amphibious vehicles taking Canadian troops across the Scheldt in Holland, during World War II |

Canada's participation in the First World War helped to foster a sense of Canadian

nationhood. The highpoint of Canadian military achievement came at the Battle of

Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917, in which the Canadian Corps captured a fortified

German hill that had resisted British and French attacks earlier in the war. Battles

such as Vimy, as well as the success of Canadian flying aces including William

Barker and Billy Bishop, helped to give Canada a new sense of identity. As a result

of the war, the Canadian government became more assertive and less deferential

to British authority, because many Canadians were dismayed by what they saw as

British command failures.

nationhood. The highpoint of Canadian military achievement came at the Battle of

Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917, in which the Canadian Corps captured a fortified

German hill that had resisted British and French attacks earlier in the war. Battles

such as Vimy, as well as the success of Canadian flying aces including William

Barker and Billy Bishop, helped to give Canada a new sense of identity. As a result

of the war, the Canadian government became more assertive and less deferential

to British authority, because many Canadians were dismayed by what they saw as

British command failures.

Canada is sometimes considered to be the country hardest hit by the interwar Great Depression. The economy fell further than that of any nation other than the United States. It hit especially hard in

Western Canada, where a full recovery did not occur until the Second World War began in 1939. Hard times led to the creation of new political parties such as the Social Credit movement and the

Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, as well as popular protest in the form of the On to Ottawa Trek.

Canada's involvement in the Second World War began when Canada declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, one week after Britain. Canadian forces were involved in the failed defence of

Hong Kong, the Dieppe Raid in August 1942, the Allied invasion of Italy, and the Battle of Normandy. Of a population of approximately 11.5 million, 1.1 million Canadians served in the armed forces in

the Second World War. Many thousands more served in the merchant marines. In all, more than 45,000 gave their lives, and another 55,000 were wounded. Countless others shared the suffering and

hardship of war. By the end of the war, Canada had, temporarily at least, become a significant military power. However, the Big Three paid little attention to Canada.

Conscription legislation was enacted during both wars (though on the initial promise of home-front service only in World War II), leading to increased tension between French and English Canadians.

During the First World War, Prime Minister Robert Borden's government enfranchised women who had close male relatives serving overseas, in the hopes of securing their support in the 1917 federal

election.

1945–1960

Main article: History of Canada (1945-1960)

Prosperity returned to Canada during Second World War. With continued Liberal governments, national policies increasingly turned to social welfare, including universal health care, old-age pensions,

and veterans' pensions.

The financial crisis of the Great Depression, soured by rampant corruption, had led Newfoundlanders to relinquish responsible government in 1934 and become a crown colony ruled by a British

governor. Prosperity returned when the U.S. military arrived in 1941 with over 10,000 soldiers and huge investments in air and naval bases. Popular sentiment grew favourable toward the United

States, alarming the Canadian government, which now wanted Newfoundland to enter into confederation instead of joining with the U.S. In 1948, the British government gave voters three Referendum

choices: remaining a crown colony, returning to Dominion status (that is, independence), or joining Canada. Joining the U.S. was not made an option. After bitter debate Newfoundlanders voted to join

Canada in 1949 as a province.[6]

Canada's foreign policy during the Cold War was closely tied to that of the U.S., which was demonstrated by membership in NATO, sending combat troops into the Korean War, and establishing a joint

air defence system (NORAD) with the U.S.

1960–1981

Main article: History of Canada (1960-1981)

In the 1960s, a Quiet Revolution took place in Quebec, overthrowing the old establishment which centred on the Catholic Church and modernizing the economy and society. Québécois nationalists

demanded independence, and tensions rose until violence erupted during the 1970 October Crisis. During his long tenure in the office (1968–79, 1980–84), Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made social

and cultural change his political goal for Canada.

Western Canada, where a full recovery did not occur until the Second World War began in 1939. Hard times led to the creation of new political parties such as the Social Credit movement and the

Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, as well as popular protest in the form of the On to Ottawa Trek.

Canada's involvement in the Second World War began when Canada declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, one week after Britain. Canadian forces were involved in the failed defence of

Hong Kong, the Dieppe Raid in August 1942, the Allied invasion of Italy, and the Battle of Normandy. Of a population of approximately 11.5 million, 1.1 million Canadians served in the armed forces in

the Second World War. Many thousands more served in the merchant marines. In all, more than 45,000 gave their lives, and another 55,000 were wounded. Countless others shared the suffering and

hardship of war. By the end of the war, Canada had, temporarily at least, become a significant military power. However, the Big Three paid little attention to Canada.

Conscription legislation was enacted during both wars (though on the initial promise of home-front service only in World War II), leading to increased tension between French and English Canadians.

During the First World War, Prime Minister Robert Borden's government enfranchised women who had close male relatives serving overseas, in the hopes of securing their support in the 1917 federal

election.

1945–1960

Main article: History of Canada (1945-1960)

Prosperity returned to Canada during Second World War. With continued Liberal governments, national policies increasingly turned to social welfare, including universal health care, old-age pensions,

and veterans' pensions.

The financial crisis of the Great Depression, soured by rampant corruption, had led Newfoundlanders to relinquish responsible government in 1934 and become a crown colony ruled by a British

governor. Prosperity returned when the U.S. military arrived in 1941 with over 10,000 soldiers and huge investments in air and naval bases. Popular sentiment grew favourable toward the United

States, alarming the Canadian government, which now wanted Newfoundland to enter into confederation instead of joining with the U.S. In 1948, the British government gave voters three Referendum

choices: remaining a crown colony, returning to Dominion status (that is, independence), or joining Canada. Joining the U.S. was not made an option. After bitter debate Newfoundlanders voted to join

Canada in 1949 as a province.[6]

Canada's foreign policy during the Cold War was closely tied to that of the U.S., which was demonstrated by membership in NATO, sending combat troops into the Korean War, and establishing a joint

air defence system (NORAD) with the U.S.

1960–1981

Main article: History of Canada (1960-1981)

In the 1960s, a Quiet Revolution took place in Quebec, overthrowing the old establishment which centred on the Catholic Church and modernizing the economy and society. Québécois nationalists

demanded independence, and tensions rose until violence erupted during the 1970 October Crisis. During his long tenure in the office (1968–79, 1980–84), Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made social

and cultural change his political goal for Canada.

| World wars Main article: Canada in the World Wars and Interwar Years |

| Signing of the initialization of the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1992 by representatives of the Canadian, Mexican, and United States governments. |

1982-1992

Main article: History of Canada (1982-1992)

In 1982, the Canada Act was passed by the British parliament and granted Royal

Assent by Queen Elizabeth II on March 29, while the Constitution Act was passed by

the Canadian parliament and granted Royal Assent by the Queen on April 17, thus

patriating the Constitution of Canada. Previously, the constitution has existed only

as an act passed of the British parliament, and was not even physically located in

Canada. At the same time, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was added in place

of the previous Bill of Rights. The patriation of the constitution was Trudeau's last

major act as Prime Minister; he resigned in 1984.

The Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney began efforts to

recognize Quebec as a "distinct society" and end western alienation. The National

Energy Program was scrapped and in 1987, talks began with Quebec to officially

have Quebec sign the Canadian Constitution. Under Mulroney, relations with the

United States improved and both Canada and the U.S. began to grow more closely

integrated. In 1986, Canada and the U.S. signed the Acid Rain Treaty to reduce acid

rain. In 1989, the federal government adopted the Free Trade Agreement with the

United States despite significant animosity from the Canadian public who were

concerned about the economic and cultural impacts of close integration with the

United States.

The Oka crisis in 1990, in which the Canadian armed forces was sent in to stop a

protest by aboriginals who refused to allow the building of a golf club on land

claimed by aboriginals.

Main article: History of Canada (1982-1992)

In 1982, the Canada Act was passed by the British parliament and granted Royal

Assent by Queen Elizabeth II on March 29, while the Constitution Act was passed by

the Canadian parliament and granted Royal Assent by the Queen on April 17, thus

patriating the Constitution of Canada. Previously, the constitution has existed only

as an act passed of the British parliament, and was not even physically located in

Canada. At the same time, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was added in place

of the previous Bill of Rights. The patriation of the constitution was Trudeau's last

major act as Prime Minister; he resigned in 1984.

The Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney began efforts to

recognize Quebec as a "distinct society" and end western alienation. The National

Energy Program was scrapped and in 1987, talks began with Quebec to officially

have Quebec sign the Canadian Constitution. Under Mulroney, relations with the

United States improved and both Canada and the U.S. began to grow more closely

integrated. In 1986, Canada and the U.S. signed the Acid Rain Treaty to reduce acid

rain. In 1989, the federal government adopted the Free Trade Agreement with the

United States despite significant animosity from the Canadian public who were

concerned about the economic and cultural impacts of close integration with the

United States.

The Oka crisis in 1990, in which the Canadian armed forces was sent in to stop a

protest by aboriginals who refused to allow the building of a golf club on land

claimed by aboriginals.

1992-Present

Main article: History of Canada (1992-Present)

In the 1990s, anger in predominantly French-speaking Quebec with the failure of constitutional reform talks, and the rising sense of alienation in Canada's western provinces due to the government's

preoccupation with attempting to convince Quebec's government to officially endorse the Constitution. After Mulroney resigned as Prime Minister in 1993, Kim Campbell took over and became

Canada's first woman Prime Minister. Campbell only remained in office for a few months and the 1993 election saw the collapse of the Progressive Conservative Party from government to only 2 seats,

while two new regional political parties: the Quebec-based sovereigntist Bloc Québécois became the official opposition and the largely Western Canada-supported Reform Party of Canada took most

of Canada's western ridings. In 1995, the government of Quebec held a second referendum on sovereignty in 1995 that was rejected by a slimmer margin of just 50.6% to 49.4%.[7] In 1997, the

Canadian Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession by a province to be unconstitutional, and Parliament passed the Clarity Act outlining the terms of a negotiated departure.[7]

The 1990s was a period of economic turmoil in Canada as Canada suffered from high unemployment in the early 1990s and a large debt and deficit that had been accumulating for years. Both

Progressive Conservative and Liberal governments in the federal government and Progressive Conservative governments in Alberta and Ontario made major cutbacks in social welfare spending and

significant privatization of government-provided services, government-owned corporations (crown corporations), and utilities occurred during this period as a means to end government deficit and

reduce government debt.

In 1995, a controversial standoff in Ipperwash, Ontario resulted in an aboriginal protester being shot dead and a subsequent inquiry discovered prevalent racism amongst the police officers involved in

the standoff. Despite this a number of high-profile changes occurred to improve aboriginal rights, such as the signing of the Nisga'a Final Agreement, a treaty between the Nisga'a people, the

provincial government of British Columbia and the federal government signed in 1999 which resolved land claims issues. The federal government responded to demands by the Arctic Inuit people for

self-governance and in 1999 granted the creation of the territory of Nunavut, which allowed the Inuktitut language to be an official language of the new territory.

In the 2000s, significant social and political changes have occurred in Canada. Canada's border control policy and foreign policy were altered as a result of the political impact of the September 11,

2001 attacks on the United States in 2001 resulting in increased pressure from the U.S. and adoption by Canada of initiatives to secure Canada's side of the border to the U.S. and Canada supported

U.S.-led military action in Afghanistan. Canada did not support the U.S.-led war in Iraq in 2003 which led to increased political animosity between the Canadian and U.S. governments at the time.

Environmental issues increased in importance in Canada resulting in the signing of the Kyoto Accord on climate change by Canada's Liberal government in 2002 but recently nullified by the present

government which has proposed a "made-in-Canada" solution to climate change. A merger of the Canadian Alliance and PC Party into the Conservative Party of Canada was completed in 2003,

ending a ten year division of the conservative vote, and was elected as a minority government under the leadership of Stephen Harper in the 2006 federal election, ending thirteen years of Liberal party

dominance in elections.

In 2006, the House of Commons passed a motion recognizing the Québécois as a nation within Canada, and,

in 2008, the Prime Minister officially apologized on behalf of the sitting Cabinet for the endorsement by previous cabinets of residential schools for Canada's aboriginal peoples, which had promoted

forced cultural assimilation oppression of aboriginal culture, and in which physical and emotional abuse took place. Canada's aboriginal leaders accepted the apology.

Main article: History of Canada (1992-Present)

In the 1990s, anger in predominantly French-speaking Quebec with the failure of constitutional reform talks, and the rising sense of alienation in Canada's western provinces due to the government's

preoccupation with attempting to convince Quebec's government to officially endorse the Constitution. After Mulroney resigned as Prime Minister in 1993, Kim Campbell took over and became

Canada's first woman Prime Minister. Campbell only remained in office for a few months and the 1993 election saw the collapse of the Progressive Conservative Party from government to only 2 seats,

while two new regional political parties: the Quebec-based sovereigntist Bloc Québécois became the official opposition and the largely Western Canada-supported Reform Party of Canada took most

of Canada's western ridings. In 1995, the government of Quebec held a second referendum on sovereignty in 1995 that was rejected by a slimmer margin of just 50.6% to 49.4%.[7] In 1997, the

Canadian Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession by a province to be unconstitutional, and Parliament passed the Clarity Act outlining the terms of a negotiated departure.[7]

The 1990s was a period of economic turmoil in Canada as Canada suffered from high unemployment in the early 1990s and a large debt and deficit that had been accumulating for years. Both

Progressive Conservative and Liberal governments in the federal government and Progressive Conservative governments in Alberta and Ontario made major cutbacks in social welfare spending and

significant privatization of government-provided services, government-owned corporations (crown corporations), and utilities occurred during this period as a means to end government deficit and

reduce government debt.

In 1995, a controversial standoff in Ipperwash, Ontario resulted in an aboriginal protester being shot dead and a subsequent inquiry discovered prevalent racism amongst the police officers involved in

the standoff. Despite this a number of high-profile changes occurred to improve aboriginal rights, such as the signing of the Nisga'a Final Agreement, a treaty between the Nisga'a people, the

provincial government of British Columbia and the federal government signed in 1999 which resolved land claims issues. The federal government responded to demands by the Arctic Inuit people for

self-governance and in 1999 granted the creation of the territory of Nunavut, which allowed the Inuktitut language to be an official language of the new territory.

In the 2000s, significant social and political changes have occurred in Canada. Canada's border control policy and foreign policy were altered as a result of the political impact of the September 11,

2001 attacks on the United States in 2001 resulting in increased pressure from the U.S. and adoption by Canada of initiatives to secure Canada's side of the border to the U.S. and Canada supported

U.S.-led military action in Afghanistan. Canada did not support the U.S.-led war in Iraq in 2003 which led to increased political animosity between the Canadian and U.S. governments at the time.

Environmental issues increased in importance in Canada resulting in the signing of the Kyoto Accord on climate change by Canada's Liberal government in 2002 but recently nullified by the present

government which has proposed a "made-in-Canada" solution to climate change. A merger of the Canadian Alliance and PC Party into the Conservative Party of Canada was completed in 2003,

ending a ten year division of the conservative vote, and was elected as a minority government under the leadership of Stephen Harper in the 2006 federal election, ending thirteen years of Liberal party

dominance in elections.

In 2006, the House of Commons passed a motion recognizing the Québécois as a nation within Canada, and,

in 2008, the Prime Minister officially apologized on behalf of the sitting Cabinet for the endorsement by previous cabinets of residential schools for Canada's aboriginal peoples, which had promoted

forced cultural assimilation oppression of aboriginal culture, and in which physical and emotional abuse took place. Canada's aboriginal leaders accepted the apology.

See also

Territorial evolution of Canada

List of Canadian monarchs

History of monarchy in Canada

List of conflicts in Canada

The Famous Five (Canada)

Science and technology in Canada

Economic history of Canada

History of medicine in Canada

Ethnic groups in Canada

List of Canadian historians

History of the United Kingdom

History of England

History of France

History of North America

History of present-day nations and

states

History of the petroleum industry in

Canada

The Fight for Canada: Four Centuries of

Resistance to American Expansionism

External links

The Canadian Museum of Civilization—

History Section

"Living History," an NFB educational site

Canada from The Canadian

Encyclopedia

Territorial evolution of Canada

List of Canadian monarchs

History of monarchy in Canada

List of conflicts in Canada

The Famous Five (Canada)

Science and technology in Canada

Economic history of Canada

History of medicine in Canada

Ethnic groups in Canada

List of Canadian historians

History of the United Kingdom

History of England

History of France

History of North America

History of present-day nations and

states

History of the petroleum industry in

Canada

The Fight for Canada: Four Centuries of

Resistance to American Expansionism

External links

The Canadian Museum of Civilization—

History Section

"Living History," an NFB educational site

Canada from The Canadian

Encyclopedia

Film, television and culture

Canada: A People's History

Canadian pioneers in early Hollywood

History of Canadian animation

History of cinema in Canada

Postage stamps and postal history of

Canada

Notes

^ The Canadian Encyclopedia,

Tadoussac, retrieved 1 September

2007.

^ a b c d e f g h i John Herd Thompson

and Stephen J. Randall, Canada and

the United States: Ambivalent Allies

(Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia

Press, 2002), 19-24

^ Romney, Paul (1999). Getting it

Wrong: How Canadians Forgot Their

Past and Imperilled Confederation.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

p.78

^ The Crown in Canada

^ Farthing, John; Freedom Wears a

Crown; Toronto, 1957

^ Karl Mcneil Earle, "Cousins of a Kind:

The Newfoundland and Labrador

Relationship with the United States",

American Review of Canadian Studies,

Vol. 28, 1998

^ a b Dickinson, John Alexander; Young,

Brian (2003). A Short History of Quebec,

3rd edition, Montreal: McGill-Queen's

University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2450-9.

Canada: A People's History

Canadian pioneers in early Hollywood

History of Canadian animation

History of cinema in Canada

Postage stamps and postal history of

Canada

Notes

^ The Canadian Encyclopedia,

Tadoussac, retrieved 1 September

2007.

^ a b c d e f g h i John Herd Thompson

and Stephen J. Randall, Canada and

the United States: Ambivalent Allies

(Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia

Press, 2002), 19-24

^ Romney, Paul (1999). Getting it

Wrong: How Canadians Forgot Their

Past and Imperilled Confederation.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

p.78

^ The Crown in Canada

^ Farthing, John; Freedom Wears a

Crown; Toronto, 1957

^ Karl Mcneil Earle, "Cousins of a Kind:

The Newfoundland and Labrador

Relationship with the United States",

American Review of Canadian Studies,

Vol. 28, 1998

^ a b Dickinson, John Alexander; Young,

Brian (2003). A Short History of Quebec,

3rd edition, Montreal: McGill-Queen's

University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2450-9.

Further reading

See Bibliography of Canadian History for an extensive list of sources.

The Dictionary of Canadian Biography(1966-2006), thousands of scholarly biographies of those who died by 1930

Bercuson, David J., Canada and the Burden of Unity (MacMillan, 1977).

Bercuson, David J., The Collins dictionary of Canadian history: 1867 to the present, 1988.

Bercuson, David J. & Granatstein, J. L., Dictionary of Canadian Military History (Oxford University Press, 1994).

Bercuson, David J. & Granatstein, J. L., War and Peacekeeping, 1990.

Bliss, Michael. Northern Enterprise: Five Centuries of Canadian Business. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1987.

Brune, Nick and Sweeny, Alastair. History of Canada Online. Waterloo: Northern Blue Publishing, 2005.

Bumsted, J.M. The Peoples of Canada: A Pre-Confederation History; and The Peoples of Canada: A Post-Confederation History. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Conrad, Margaret and Finkel, Alvin. Canada: A National History. Toronto: Pearson Education Canada, 2003.

Conrad, Maragaret and Finkel, Alvin eds. Foundations: Readings in Post-Confederation Canadian History. and Nation and Society: Readings in Post-Confederation Canadian History. Toronto: Pearson

Longman, 2004. articles by scholars

Costain, Thomas B., The White and the Gold: The French Regime in Canada (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co, Inc., 1960).

Dickason, Olive P. Canada's First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times (2001).

Francis, R. Douglas & Smith, Donald B., eds., Readings in Canadian History 3rd ed (1990).

Who Killed Canadian History? / Jack Granatstein (2007) ISBN 0002008955

Hallowell, Gerald, ed. The Oxford Companion to Canadian History (2004) 1650 short entries

Marsh, James C., ed. The Canadian Encyclopedia 4 vol 1985; also cd-rom editions

McKay, Ian, Rebels, Reds, Radicals: Rethinking Canada's Left History, Between the lines 2006, ISBN 1896357970

Morton, Desmond. A Short History of Canada 5th ed (2001)

Morton, Desmond. A Military History of Canada (1999)

Morton, Desmond. Working People: An Illustrated History of the Canadian Labour Movement (1999)

Norrie K. H. and Owram, Doug. A History of the Canadian Economy, 1991

Pryke, Kenneth G. and Soderlund, Walter C., eds. Profiles of Canada. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2003. 3rd edition.

Taylor, M. Brook, ed. Canadian History: A Reader's Guide. Vol. 1.

Owram, Doug, ed. Canadian History: A Reader's Guide. Vol. 2. Toronto: 1994. historiography

Statistics Canada. Historical Statistics of Canada. 2d ed., Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1983.

Canadawiki features hundreds of stories from Canadian History as well as the CanText text library and CanLine Chronology of Canadian History.

Thorner, Thomas and Frohn-Nielsen, Thor, eds. "A Few Acres of Snow": Documents in Pre-Confederation Canadian History, and "A Country Nourished on Self-Doubt": Documents on

Post-Confederation Canadian History, 2nd ed. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2003.

Wade, Mason, The French Canadians, 1760-1945 (1955) 2 vol

See Bibliography of Canadian History for an extensive list of sources.

The Dictionary of Canadian Biography(1966-2006), thousands of scholarly biographies of those who died by 1930

Bercuson, David J., Canada and the Burden of Unity (MacMillan, 1977).

Bercuson, David J., The Collins dictionary of Canadian history: 1867 to the present, 1988.

Bercuson, David J. & Granatstein, J. L., Dictionary of Canadian Military History (Oxford University Press, 1994).

Bercuson, David J. & Granatstein, J. L., War and Peacekeeping, 1990.

Bliss, Michael. Northern Enterprise: Five Centuries of Canadian Business. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1987.

Brune, Nick and Sweeny, Alastair. History of Canada Online. Waterloo: Northern Blue Publishing, 2005.

Bumsted, J.M. The Peoples of Canada: A Pre-Confederation History; and The Peoples of Canada: A Post-Confederation History. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Conrad, Margaret and Finkel, Alvin. Canada: A National History. Toronto: Pearson Education Canada, 2003.

Conrad, Maragaret and Finkel, Alvin eds. Foundations: Readings in Post-Confederation Canadian History. and Nation and Society: Readings in Post-Confederation Canadian History. Toronto: Pearson

Longman, 2004. articles by scholars

Costain, Thomas B., The White and the Gold: The French Regime in Canada (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co, Inc., 1960).

Dickason, Olive P. Canada's First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times (2001).

Francis, R. Douglas & Smith, Donald B., eds., Readings in Canadian History 3rd ed (1990).

Who Killed Canadian History? / Jack Granatstein (2007) ISBN 0002008955

Hallowell, Gerald, ed. The Oxford Companion to Canadian History (2004) 1650 short entries

Marsh, James C., ed. The Canadian Encyclopedia 4 vol 1985; also cd-rom editions

McKay, Ian, Rebels, Reds, Radicals: Rethinking Canada's Left History, Between the lines 2006, ISBN 1896357970

Morton, Desmond. A Short History of Canada 5th ed (2001)

Morton, Desmond. A Military History of Canada (1999)

Morton, Desmond. Working People: An Illustrated History of the Canadian Labour Movement (1999)

Norrie K. H. and Owram, Doug. A History of the Canadian Economy, 1991

Pryke, Kenneth G. and Soderlund, Walter C., eds. Profiles of Canada. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2003. 3rd edition.

Taylor, M. Brook, ed. Canadian History: A Reader's Guide. Vol. 1.

Owram, Doug, ed. Canadian History: A Reader's Guide. Vol. 2. Toronto: 1994. historiography

Statistics Canada. Historical Statistics of Canada. 2d ed., Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1983.

Canadawiki features hundreds of stories from Canadian History as well as the CanText text library and CanLine Chronology of Canadian History.

Thorner, Thomas and Frohn-Nielsen, Thor, eds. "A Few Acres of Snow": Documents in Pre-Confederation Canadian History, and "A Country Nourished on Self-Doubt": Documents on

Post-Confederation Canadian History, 2nd ed. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2003.

Wade, Mason, The French Canadians, 1760-1945 (1955) 2 vol

| An animated GIF of the evolution of Canada's internal borders, from the formation of the dominion to the present. |